The Science of Nocebo, Placebo, Iatrogenesis and Evidence Based Yoga

Clinical Yoga

Clinical yoga is essentially physiotherapist instructed yoga, designed with an evidence based framework, taught individually, with a biopsychosocial focus and neuroscientific understanding.

This approach to treatment is founded on an understanding of the neuroscience behind the patient-therapist relationship:

There are certain behaviours and brain mechanisms that are initiated by an individual who experiences pain or illness. There are four steps depicted in this scheme, and all can be approached from a neuroscientific point of view.

Adapted from Benedetti (2014)

Suggestibility

Suggestibility is the quality of being inclined to accept and act on the suggestions of others; where false but plausible information is given, and one fills in the gaps with false information [1].

Suggestibility uses cues to distort perception after persistently being told something pertaining to an experience, one's perception of stimulus conforms to what they've been told. [2]

A person experiencing intense emotions tends to be more receptive to ideas and therefore more suggestible [3]. Psychologists have found that individual levels of self-esteem and assertiveness can make some people more suggestible than others, which has resulted in the concept of a spectrum of suggestibility [4].

Its role in the pain cycle

To understand how suggestibility may influence pain, it is crucial to appreciate three fundamental phenomenon:

Placebo Analgesia: Endogenous pain relief due to an expectation of reduced pain by verbal suggestion, or manipulation of environment [5].

Nocebo Hyperalgesia: The transformation of very low level painful stimulus into high intensity pain due to verbal suggestion (or another cue) of increased pain [6].

Nocebo Allodynia: The transformation of completely non-painful stimulus into pain due to a manipulation of expectation, from either verbal suggestion or another environmental factor [7].

These terms describe the way in which several complex psychosocial factors may activate different neurotransmitters and different systems.

Experimental studies

Verbal suggestions of pain increase were given to healthy volunteers before administration of either tactile or low-intensity painful electrical stimuli.

It was found that verbal suggestions alone turned:

Tactile stimuli into pain, and;

Low-intensity painful stimuli into high-intensity pain [7]

Sawamoto et al studied the brains of people under these same conditions, and discovered that pain induced through verbal suggestion activates the same brain regions as an actual painful stimulus itself [8].

Pain relates to perceived threat

Verbal suggestion can influence pain due to anticipation of pain. The same is true in conditions whereby environmental cues transmit supposedly meaningful information.

With some prior conditioning, a sham headache simulator can reliably induce headache pain, with pain scores increasing as settings on the sham simulator are increased [9].

Similarly, a -20°C rod will be perceived as hot if coupled with a red visual cue, but perceived as cold if coupled with a blue visual cue. The rod is perceived as more painful with a red cue than blue cue. The subjects also reported more pain if they looked at the rod being applied than if they didn’t (relating to anticipation increasing pain) [10].

Chronic neck pain can be manipulated by altering input from the visual system. In one study, patients performed head rotation to their first onset of pain, in three virtual-reality conditions where the amount of rotation that they saw did not match reality. Instead, the viewed rotation was more or less than was actually occurring, creating an illusion of movement that was different to actual movement. Remarkably, pain with movement depended not only on how far people actually moved, but how far it appeared they had moved [11].

Real world examples

THAI VEGETARIAN FESTIVAL

The Thai Vegetarian festival is a very interesting example of cortical regulation of pain.

The festival typically involves ritualized mutilation, all without anaesthetic. Interestingly, the devotees report no pain during this procedure, and typically return to daily activities occurs shortly after the completion of the ritual [12].

This process is, in a sense, representative of how POSITIVE AFFECTIVITY reduces pain perception, and reduces the psychological trauma associated with injury. The social, cultural and environmental context surrounding this activity helps to shape neural processes that alter the devotees moment to moment experience. I.e. the trauma occurs in a positive context, and is a open display of veneration for their gods and ancestors, and a display their devotion to their beliefs and the meditative trance itself.

The devotees, anecdotally report a profound impact upon demeanour for days or weeks after, frequently with devotees appearing exceptionally calm and focused in their day-to-day activities after the festival is completed.

An example of nocebo allodynia through cortical-attentional mechanisms

“A builder aged 29 came to the accident and emergency department having jumped down on to a 15 cm nail. As the smallest movement of the nail was painful he was sedated with fentanyl and midazolam. The nail was then pulled out from below. When his boot was removed a miraculous cure appeared to have taken place. Despite entering proximal to the steel toecap the nail had penetrated between the toes: the foot was entirely uninjured.”

REFERENCE:

Fisher JP, Hassan DT, O’Connor N. Minerva. BMJ. 1995 Jan 7;310(70). [13]

This process is, in a sense, representative of how NEGATIVE AFFECTIVITY increases pain perception, and increases the psychological trauma associated with injury. The social, cultural and environmental context surrounding this work incident helped to shape neural processes that altered the workers conscious pain experience. I.e. the incident is representative of potential Job security/livelihood issues, subsequent potential, Financial distress, fears of permanent injury, Worries for family etc.

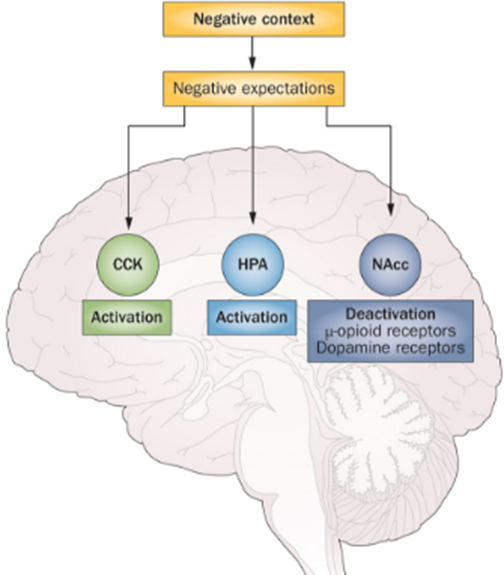

Psychological framework [14]

Neuroscientific Framework [15]

LEGEND:

CCK:

Cholecystokinin (CCK) has been strongly linked to anxiety and panic

HPA:

The hypothalamic, pituitary, adrenal (HPA) axis is our central stress response system. Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) plays a central role in the stress response by regulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

NAcc:

Nucleus Accumbens. Endogenous opioid release. Active in the placebo effect

Verbal cues in everyday clinical conversations

Given this data, clinicians need to prudently, judiciously and honestly communicate with their patients, so as to inform them of these phenomenon and how they relate to the pain experience, such that they are well informed, more self-aware and less vulnerable to iatrogenesis through interactions with the biomedical model.

A specific example of this is the iatrogenic effects of MRI on back pain patients.

The vast majority of back pain and radiculopathy patients receive MRI within the first month of care, despite guideline recommendations to delay imaging to allow for the natural history of improvement to occur [16].

Risks of early MRI for back pain?

The receipt of early MRI for back pain and radiculopathy is associated with worse outcomes, even after controlling for severity and demographic factors.

Subsequent medical usage is also increased with MRI usage, on average costing $13,000 per patient.

Early MRI had longer work disability outcomes at 1-year follow-up.

Patients and/or physicians may misinterpret unrelated abnormalities as indicative of a more specific or severe diagnosis, and focus their attention on an abnormality to which they erroneously attribute the patient's pain.

The increase in imaging has been associated with an increase in specialist referrals and spinal surgery, without improvement in outcomes.

The diagnostic focus may also lead patients to expect a “cure” or complete recovery and lead to requests for more intensive interventions or a delay in the initiation of a functional restoration program.

Some providers plan to use MRI results as a way of reassuring patients. However, the results often lead to the opposite effect—instead of reassurance, patients develop a decreased sense of well-being.

Early MRI is the first indication of a cascade pattern of care that is characterized by overprescribing, overtesting, intensive and ineffective treatment, and ultimately, poor outcomes. [16]

Benefits of early MRI for back pain?

After screening for red flags, no benefit in health, function, or disability outcomes are associated with early MRI usage. [16]

Based on the above evidence, we can hypothesise that language, such as the language used above to describe what is, epidemiologically, a “normal” scan for an individual, can actually shape neural processes that amplify the pain one may be experiencing (from say sensitised musculature, with central mediation), and worsen outcomes in an iatrogenic manner. Additionally, the medicalization of clinically irrelevant findings lead patients' to request more intensive interventions.

Setting Expectations

Chronic back pain patients are often referred for conservative treatment by their physician with the phrasing; “you should trial a course of conservative management before considering spinal surgery”. Given what we know about verbal suggestibility, we should acknowledge that this type of cognitive framing is not optimal.

To appreciate this, it’s useful to acknowledge the below phenomenon:

Significant spinal pathology (and musculoskeletal “pathology” generally) can be reliably demonstrated on asymptomatic, fully functional individuals [17].

The brain can produce debilitating pain, and reliably reduce function, even in the absence of tissue damage. This can occur through information processing in the brain (verbally induced hyperalgesia, nocebo allodynia via faulty beliefs about external reality), brain related changes in the PFC (Epigenetic modulation by DNA methylation is associated with abnormal behaviour and pathological gene expression in the central nervous system), life events (stress producing neurochemical changes in the brain and cortical sensitisation) [18].

Success or failure of conservative management is typically predicated on subjective pain scores (patient self-report) and functional status [19].

There is, incidentally, no good evidence to support the use of surgical interventions [20], injections [21], or opioid use [22] for chronic back pain.

When does an episode of exacerbation of pain and reduced function testify to the origin of that pain being from spinal pathology in isolation? It is currently clear that:

Spinal pathology on imaging reliably does not cause symptoms

Central processing and nervous system related changes can reliably produces pain, and correlate with the duration and intensity of pain.

Life stressors and other environmental influences are in a state of flux, and thereby cognitive status is at risk of being in a state of flux, meaning symptoms and functional status, by extension, can also be in a state of flux, independent of the status of the spine under imaging.

With the statement “we’ll trial conservative management first to try and avoid surgery” or any incarnation of this, the clinician may have incidentally seeded in patients mind the expectation that any fluctuation to an increase in pain score or decreased function (perceived failure of conservative management) is, “sequitur ex praemissis”, an indication for surgery. This result follows from the initial premise that the clinician linguistically orchestrated from the outset.

If someone wants to engage in patient “shared decision making”, a better option is to educate the patient with transparent, honest information aimed at increasing health literacy, promoting truly informed decision making.

This would include educating the patient about the role of a targeted approach to managing stable cognitive status. Cognitive status being influenced by:

Physical health

Accessibility of enriched environments that promote activity

Insight and self awareness

Psychosomatosensory integration [23]

So why hasn’t new research on pain science changed medical practice?

What we are witnessing is three phenomenon:

Increasing evidence that certain medical interventions given to patients in the community for pain (injections, surgeries etc) do not work better than sham injections or sham surgeries (i.e. evidence from double blind RCT’s) [24].

An increasing understanding of neuroscience behind pain, the biopsychosocial inputs, and the efficacy of certain conservative biopychosocial oriented approaches [25].

A paradoxical year-on-year growth in the number of scientifically unsupported medical interventions being performed for pain relief [26].

There are many likely explanations. Firstly, it is standard practice, so it is easy to justify; if everyone is doing it, then you cannot be criticised for doing it. Also, many pain patients just want some kind of treatment and at least the doctors feel as if they are “doing something”.

More concerning than that, however, is that even in so called “pain management clinics”, there still appears to be a reductionist bias, and, instead of changing practice, it’s apparent that some medical clinics have co-opted the biopsychosocial model to perpetuate high cost, low value technological treatments.

For example, it’s possible to appear as though you are integrating the biopsychosocial model, by offering “multidisciplinary treatment”, but, if it’s delivered on a hierarchal basis, then each member of the team has, by necessity, a narrower and narrower focus, reduced autonomy, and subservience to new technology (there is a bias for us to assume the “new” is better, combined with an unskeptical approach to new technology, and a general overestimation of the benefits and underestimation of the harms of invasive treatments).

Medications, Nerve blocks, Joint blocks, Radiofrequency, Neurostimluation, Ketamine Infusions and Opioid prescriptions are offered medically, while self management, graduated exercise, functional strategies, pain education etc can be too easily relegated or made to play a subservient role, given the hierarchal structure of a private clinic owned by medicos. And, of course, it’s no surprise that you can charge a lot more money for invasive treatment…

There is the problem of reliable evidence, with invasive procedures mentioned not compared to sham treatments, so no way of knowing if they works beyond the level of the placebo, yet risks are higher and costs significantly higher.

The psychological implications for patients are significant, as pain patients who don’t respond initially to conservative treatment are liable to see the subsequently escalating invasive medical steps as chronological, reinforcing the belief that there is;

A biomedical basis for their suffering;

A quick fix offer on the table,

A purely passive treatment option in the pipeline , and;

This cognitive framing is reinforced with the paternalistic structure of such establishments.

These particular multidisciplinary clinics I see as employing just another form of reductionism, operating under the guise of the biopsychosocial model.

The conventional private practice physiotherapy business model also struggles to effectively treat persistent pain, and is notably acquiescent to the biomedical model…

Overall, the amount of medical waste in the system at the moment (in the form of unwarranted and expensive scans, specialist referrals and non-evidence supported but expensive invasive interventions etc) is huge, and pain management has not changed adequately, despite our advancements in pain science knowledge.

For example, a consensus statement from the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) this year (2016) noted that exercise should be a mainstay of therapy for the treatment of fibromyalgia. Additionally, the group concensus did not endorse most pharmaceutical interventions, especially drugs with a high potential for abuse [27]. It’s doubtful that this will change prescribing behaviour in rheumatology practice anytime soon however.

Graduated, mindful movement based approaches that emphasise decreasing fear about movement, increasing self-efficacy, self-understanding and self-empowerment, explaining pain physiology, empathetic patient-centred communication, demystifying beliefs about pain (beliefs which for the most part come from patients interactions with health care practitioners), increasing patient’s health/scientific literacy, addressing psychological comorbidities etc have been replicated in the literature as effective evidenced based treatments [25].

The problem is that this evidence has still not shifted clinical practice and clinical business models in many cases. Many practitioners are simply at a loss to know how to integrate this information and pragmatically utilize the biopsychosocial model.

A useful framework for this paradigm shift has been captured with recent studies examining “Cognitive functional therapy”, and its broad reach in addressing the biological, psychological and social aspects contributing to pain. This can be used as a foundation to structure conservative exercise based educational treatments.

Pain in contemplative traditions

In medieval Europe, during the Christendom, pain was seen as a punishment for sin. Christians were burning “witches” and heretics alive in the 11th century. Meanwhile, contemplative traditions of the east, as revealed in the Vedas and Upanishads, were engaged in sophisticated discourses about the emotive aspects of pain, and the role of conditioning in perpetuating it. The notion of false apprehension of reality and incorrect knowledge leading to suffering are paramount in these texts.

The Buddha’s discourses on right speech, right action, right living, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration, leading to 'insight, knowledge, calm, higher knowledge, enlightenment, and nibbana’ are particulary relevant.

The Buddha discussed the four noble truths:

'This is pain''.

“This is the origin of pain”.

“This is the ending of pain”.

“This is the way leading to the ending of pain.”

Pain, as a subjective emotional experience, as outlined in the Vedas and Upanishads is not incorrect- changes to our subjective state is all we have, and all we could possibly care about. As for our current “Modus Operandi”, historically, in the West, the “spiritual” is associated with something external and lifted up; thus the high and raised up altar and cross in Christian churches.

In an Eastern Shiva temple, however, the spiritual symbol, the lingam, is often sunk in a deep shaft several meters below ground level [28].

According to Carl Jung, this indicated that in “Eastern” experience, the spiritual is to be found in the inward direction, in the deepest and darkest place. In his Psychology of Eastern Meditation he makes the following point:

“The West is always seeking uplift, but the East seeks a sinking or deepening. Outer reality, with its bodiliness and weight appears to make a stronger and sharper impression on the European than it does on the Indian. The European seeks to raise himself above the world, while the Indian likes to turn back to the maternal depths of nature.” Jung, 1949 [28].

It’s no surprise that, in recent years, Mindfulness Meditation and Yoga have been taken seriously, and scientifically studied in pain management [29, 30]. Here, the need is to fuse insights into ones subjectivity with objectively verifiable facts about pain.

Jung stated that, “from the Eastern perspective, the West needs to rediscover or resensitise itself to the interior aspects of intuition and feeling- but without letting go of its strong grip on exterior scientific consciousness. The East on the other hand, needs the science, industry, and technology of the West, but not at its expense of its sensitivity to the inner man. On both sides, a balanced, widened, and inclusive consciousness needs to be achieved” [28].

While this needs to be appreciated in the historical context in which it was written, it has profound implications for our treatment of pain going forward.

Jung was also fairly clear with his quote- that the introspective practices of the East need to be alloyed with the scientific method. I.e. Scientific scepticism, rational inquiry, falsifiability, third-person experimental science, respect for evidence etc.

Additionally, categorising these contemplative practices as ‘Eastern’ will, in the fullness of time, become a false dichotomy, as we gain an increased understanding of the underlying biology and neuroscience involved in these practices. Just as we don’t define Algebra as “Eastern Alberga”, or Physics as “Western Physics”, these methods will eventually fall within the purview our growing scientific understanding of the world. The bottom line is that evidence based interventions have an important place, whether they be biomedical or “Eastern”.

The case for active approaches to treatment:

Acute pain:

Active self management techniques for acute pain draw the emphasis away from the perceived need to reply on passive treatment. Any passive techniques that are actually useful can be taught to the client, to further encourage self-treatment.

Active self management avoids biomedical messages learned in the acute stage of an injury needing undoing later on.

Chronic pain:

For the patient it represents the difference between:

Yoga and Pain Science

Yoga as treatment, and the Pain Gate Theory

Pain researcher Patrick Wall was one of the early pioneers of the pain science revolution. Wall was living in a difficult era, attempting to refute decades old pain theories in both the absence of a neuroplastic framework (which may have helped his research), and in the presence of some challenging data. In Walls (1967) paper, he describes opposition to his ideas coming from (what was then considered very convincing) “psychophysical” studies that found “a precise mathematical relationship between stimulus intensity and pain intensity” [31].

He (rightly) criticised these studies, indicating that only in such “laboratory conditions”, a relatively “fixed line transmission system prevails”. He tried to counter this by citing Beecher’s (1959) article that examined wounded American soldiers who “entirely denied pain from their extensive wounds”, presumably because they were "overjoyed" at having escaped alive from the battlefield [32].

He then postulated that the “amount and quality of perceived pain are determined by many psychological variables in addition to the sensory input” [31]. The paper then goes on to brilliantly describe in detail his work on gate control theory. He summaries his view by suggesting that factors such as “past experience, attention and emotion” influence pain response and perception, and that pain is susceptible to “central control”, and may allow patients to “think about something else” or “use other strategies to keep pain under control”. [31]

It’s worth noting, that in eastern thought, (with its focus on subjective empirical investigation of consciousness), this notion had been well documented as early as 200BC; “Due to the variance in the quality of mind content, each person may experience the same thing differently, according to his own way of thinking”. “Objects and experiences are either known or not known according to the way in which the colouring of that object falls on the colouring of the mind observing it.” Patanjali (200 BC) [33]

On the role of “past experience” modifying pain perception, Patanjali (200BC) explains that “Aversion is a modification that results from misery associated with some memory, whereby the three modifications of aversion, pain, and the memory of the object or experience are then associated with one another” [33]. The role of prior experience with pain in the development of expectancy induced somatoform pain (nocebo allodynia) has been objectively verified and replicated [9, 43].

Patanjali explained strategies to centrally control pain through meditation and self-inquiry “When the memory or storehouse of modifications of mind is purified, then the mind no longer taints and modifies perception. Then, only the object on which it is contemplating appears to shine forward.” [33].

Wall has essentially provided a scientific framework for how this universal subjective experience of pain is perceived, regulated, and shaped in one’s conscious experience. Wall verified the role that emotion, attention, distraction, and past experience have in modifying consciousness though complex neuroscientific mechanisms. This provides a scientifically justifiable bedrock for the biopsychosocial construct in modern medicine, and unintentionally corroborates first person subjective techniques for pain control.

The Evidence Based scaffolding of Clinical Yoga

To optimise the teaching of yoga for the chronic pain population, in a clinical setting, the following scaffolding may be embedded in one’s instruction.

1. Initial consultation:

In the vast majority of people (<90%) LBP is benign and represents a simple muscle spasm associated with a mechanical loading incident or a muscle spasm with “central mediation” associated with psychosocial or lifestyle stresses.

Only 1 to 2% of people presenting with LBP will have a serious or systemic disorder, such as systemic inflammatory disorders, infections, spinal malignancy or spinal fracture.

Less than 5% present with significant neurological deficits such as cauda equine syndrome [34].

SCREEN FOR REG FLAGS

2. Demystify scan results:

Over-imaging for LBP is endemic in primary care (Runciman et al 2012) [35]

Radiological imaging for LBP, in the absence of red flags, progressive neurological deficits and traumatic injury, is not warranted and detrimental (Deyo 2013). [34].

Advanced disc degeneration, spondylolisthesis and modic changes of the vertebral end plate do not predict future LBP (Deyo 2013; Jarvic et al 2005). [34, 36].

High prevalence of ‘abnormal’ findings on MRI in pain-free populations (disc degeneration [91%], disc bulges [56%], disc protrusion [32%], annular tears [38%]) (McCullough et al 2012) [37].

Findings correlate poorly with pain and disability levels (Deyo 2005). [36]

There is strong evidence that unwarranted imaging makes patients worse; MRI scans for nontraumatic LBP lead to poorer health outcomes, greater disability and work absenteeism due to the pathologising of the problem (Deyo 2013). [34]

3. Demystifying common beliefs about pain:

Negative beliefs about LBP are predictive of pain intensity, disability levels and work absenteeism as well as chronicity (Main et al 2010) [38]

Beliefs can independently increase disability and impair recovery (Main et al 2010):

Having a negative future outlook (e.g. ‘I know it will just get worse’)

‘Hurt equals harm’

‘Movement should be avoided’ [38]

Many of these beliefs gain their origins from healthcare practitioners (Darlow 2013; Lin 2013) highlighting the critical role of communication in the acute care of people with LBP. [39, 40].

Beliefs= filters of perception and engines of behaviour

Catastrophic thinking increases pain behaviours by increasing fear and distress (Sullivan et al 2001)

‘my back is damaged’ --> Reduce activity --> Bed rest

'Iam never going to get better’ --> increased anticipatory anxiety --> increases pain

‘I am going to end up in a wheel chair --> Catastropic thinking about pain has dramatic effects on global pain experience [41].

Pain behaviours (limping, and protective muscle guarding) then lead to:

Abnormal loading of sensitised spinal structures

Feeding a vicious cycle of pain

Poor coping styles, such as avoidance and excessive rest.

Leaves the person feeling helpless and disabled [41].

In contrast, people who have positive beliefs about LBP and its future consequences are less disabled (Main et al 2010) [38]

“Whether young or old, very old, sick or feeble, one can attain health in yoga by practising.” (Hatha Pradipika 1:64, 15th century)

4. Empathetic, patient centred communication:

Current evidence supports sensitive, patient-centred communication (Vibe Fersum 2013) [42]

This helps therapists to:

Understand patient concerns

Identify and address negative beliefs about LBP

Reassure patients regarding the benign nature of LBP

Discuss the limitations of radiological examinations: emphasise that disc degeneration, disc bulges, annular tears and facet joint arthrosis are normal in the pain-free population, are not a sign of damage or injury and do not predict outcome (Chou et al 2012) [43]

Carefully explain the biopsychosocial pain mechanisms relevant to the patient

Advise patients to keep active and normalise movement.

This sensitive, motivational communication:

Builds health literacy about LBP

Empowers patients to take an active role in their rehabilitation rather than rely on passive treatments

5. Divert attention away from the back, focus on yoga practice, movement, mindfulness

Directed attention plays a key role:

Anxiety induced hyperalgesia, pain increases as focus is on painful structures, i.e. the specific body part involved.

In stress induced analgesia, attention is directed on the environmental “stressor” (i.e. yoga practice). --> evidence of activation of endogenous opioid system.

Do yoga, not ‘core exercises’:

In contrast to popular belief, there is little evidence that LBP is associated with a loss of ‘core’ or trunk stability.

There is growing evidence that “core stability exercises” result in altered movement patterns, and increased trunk muscle co-contraction, are associated with the recurrence and persistence of LBP.

6. Movement, breathing , relaxation, mindfulness primary means of treatment

People with nonspecific LBP more commonly increase trunk muscle guarding and have stiffness, which paradoxically increases spinal loading and pain (O’Sullivan 2012). Therefore, practising relaxation of trunk muscles incorporated with graded movement training is important to unload sensitised spinal structures and allow normal movements to occur.

Graduated activity: ‘Gradually increase your activity levels based on time rather than the levels of pain’

Activity modification should only be recommended in the acute phase if there is evidence of tissue strain.

Otherwise, advice to keep active in a graded manner is important to reduce the pain avoidance vicious cycle.

Mindful exercise

Paying attention to the present moment

Attention focused on muscles

Attention focused on breathing

Any form of physical activity can integrate this inner-attentiveness or a cognitive component, however this is the key feature and process in mindful exercise

Yoga Mindfulness

MRI study of brains of 20 meditators compared to matched controls. “Brain regions associated with attention, interoception and sensory processing were thicker in meditation participants than matched controls, including the prefrontal cortex and right anterior insula” in longterm meditators” (Lazar et al., 2005)

Figure: 1. Insula, 2. Brodmann area,. 3. Somatosensory cortex, 4. Auditory cortex.

Neural mechanisms in meditation

Zeiden et al’s 2011 fMRI study comparing meditating in presence of pain vs. rest found a 40% reduction in pain and 57% reduction in pain unpleasantness

Meditation engages multiple brain mechanisms that alter the construction of the subjectively available pain experience from afferent information

Stress reduction

2008, University of Utah

Study examined three groups response to painful stimulus:

Fibromyalgia patients

Lowest pain threshold

Greatest brain activity on fMRI

Healthy volunteers

Average pain threshold

Average brain activity on fMRI

Experienced yoga practitioners

Highest pain threshold

Lowest brain activity on fMRI

Mechanism explained

Yoga promotes growth in brain regions for self-awareness

fMRI detected:

More grey matter—brain cells—in certain brain areas in people who regularly practiced yoga, as compared with control subjects.

+ve correlation between hours of yoga practiced/week and grey matter enlargement.

Yogis had larger brain volume in the somatosensory cortex, which contains a mental map of our body, the superior parietal cortex, involved in directing attention, and the visual cortex.

The hippocampus, a region critical to dampening stress, was also enlarged in practitioners

The posterior cingulate cortex, key to our concept of self was enlarged.

Mindful movement vs seated meditation

A study of MBSR found that the total time spent doing mindful movement (yoga) was more strongly related to increases in mindfulness and decreases in psychological distress than other mindfulness practices like body scanning and sitting meditation

(Carmody, J., & Baer, R. a. (2008). Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31, 23– 33.)

Additive benefits of mindfulness in motion

“By moving in a mindful way, there may be an additive effect of training as the two elements of the practice (mindfulness and movement) independently, and perhaps synergistically, engage common underlying systems (the default mode network)”

(Russell, T. A., & Arcuri, S. M. (2015). A Neurophysiological and Neuropsychological Consideration of Mindful Movement: Clinical and Research Implications. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, 1-17)

Psychological changes

Increased awareness of mental and physical states, which may help patients better understand their pain.

Yoga has also been shown to increase the frequency of positive emotions , which could potentially undo the physiological effects of negative emotions, broaden cognitive processes (e.g., taking a broader perspective on problems), and build physical (e.g., improved sense of health), social (e.g., improved social support) and psychological (e.g., optimism) resources.

Finally, it is possible that yoga can lead to improvements in self-efficacy for pain control.

7. Encouragement to be active in society and work

A primary aim for the management of acute LBP is the restoration of normal participation in work, family life and recreational activities, which indirectly promote confident spinal movement and functional capacity. This is crucial to facilitate a return to the whole health (physical, mental and social) of the patient.

References:

1. De Pascalis, V., Chiaradia, C., & Carotenuto, E. (2002). The contribution of suggestibility and expectation to placebo analgesia phenomenon in an experimental setting. Pain, 96(3), 393-402

2. Milling, L. S., Reardon, J. M., & Carosella, G. M. (2006). Mediation and moderation of psychological pain treatments: response expectancies and hypnotic suggestibility. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 74(2), 253.

3. Hull, C. L. (1933). Hypnosis and suggestibility.

4. Drake, K. E., Bull, R., & Boon, J. C. (2008). Interrogative suggestibility, self‐esteem, and the influence of negative life‐events. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 13(2), 299-307.

5. Levine, J., Gordon, N., & Fields, H. (1978). The mechanism of placebo analgesia. The Lancet, 312(8091), 654-657.

6. Benedetti, F., Amanzio, M., Vighetti, S., & Asteggiano, G. (2006). The biochemical and neuroendocrine bases of the hyperalgesic nocebo effect. Journal of Neuroscience, 26(46), 12014-12022.

7. Colloca, L., Sigaudo, M., & Benedetti, F. (2008). The role of learning in nocebo and placebo effects. Pain, 136(1), 211-218.

8. Sawamoto, N., Honda, M., Okada, T., Hanakawa, T., Kanda, M., Fukuyama, H., ... & Shibasaki, H. (2000). Expectation of pain enhances responses to nonpainful somatosensory stimulation in the anterior cingulate cortex and parietal operculum/posterior insula: an event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Journal of Neuroscience, 20(19), 7438-7445.

9. Bayer, T. L., Coverdale, J. H., Chiang, E., & Bangs, M. (1998). The role of prior pain experience and expectancy in psychologically and physically induced pain. Pain, 74(2), 327-331.

10. Moseley, G. L., & Arntz, A. (2007). The context of a noxious stimulus affects the pain it evokes. PAIN®, 133(1), 64-71.

11. Harvie, D. S., Broecker, M., Smith, R. T., Meulders, A., Madden, V. J., & Moseley, G. L. (2015). Bogus visual feedback alters onset of movement-evoked pain in people with neck pain. Psychological science, 26(4), 385-392.

12. Murdock, S. (2014, October 26). Thailand's Vegetarian Festival Is Painfully Awesome. Retrieved February 04, 2017, from http://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/entry/thailand-vegetarian-festival_n_6049542

13. Fisher JP, Hassan DT, O’Connor N. Minerva. BMJ. 1995 Jan 7;310(70).

14. Vlaeyen, J. W., & Linton, S. J. (2000). Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain, 85(3), 317-332.

15. Benedetti, F. (2011). The patient's brain: the neuroscience behind the doctor-patient relationship. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

16. Webster, B. S., Bauer, A. Z., Choi, Y., Cifuentes, M., & Pransky, G. S. (2013). Iatrogenic consequences of early magnetic resonance imaging in acute, work-related, disabling low back pain. Spine, 38(22), 1939-1946.

17. Siivola, S. M., Levoska, S., Tervonen, O., Ilkko, E., Vanharanta, H., & Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S. (2002). MRI changes of cervical spine in asymptomatic and symptomatic young adults. European Spine Journal, 11(4), 358-363.

18. Latremoliere, A., & Woolf, C. J. (2009). Central sensitization: a generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. The Journal of Pain, 10(9), 895-926.

19. Melzack, R., & Katz, J. (2001). The McGill Pain Questionnaire: appraisal and current status. Guilford Press.

20. Deyo, R. A., Cherkin, D., Conrad, D., & Volinn, E. (1991). Cost, controversy, crisis: low back pain and the health of the public. Annual review of public health, 12(1), 141-156.

21. Chou, R., Hashimoto, R., Friedly, J., Fu, R., Bougatsos, C., Dana, T., ... & Jarvik, J. (2015). interventions for radiculopathy: Immediate improvement in pain Figure 2. Meta-analysis of epidural corticosteroid injections versus placebo interventions for radiculopathy: Short-term improvement in pain Figure 3. Meta-analysis of epidural corticosteroid injections versus placebo interventions for radiculopathy: Intermediate-term improvement in pain. analysis, 163, 373-381.

22. Chou, R., Turner, J. A., Devine, E. B., Hansen, R. N., Sullivan, S. D., Blazina, I., ... & Deyo, R. A. (2015). The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Annals of internal medicine, 162(4), 276-286.

23. Hackman, D. A., Farah, M. J., & Meaney, M. J. (2010). Socioeconomic status and the brain: mechanistic insights from human and animal research. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(9), 651-659.

24. Hadler, N. M. (2009). Stabbed in the back: confronting back pain in an overtreated society. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

25. O'Sullivan, P. (2012). It's time for change with the management of non-specific chronic low back pain. British journal of sports medicine, 46(4), 224-227.

26. Deyo, R. A., Mirza, S. K., Turner, J. A., & Martin, B. I. (2009). Overtreating chronic back pain: time to back off?. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 22(1), 62-68.

27. Macfarlane, G. J., Kronisch, C., Dean, L. E., Atzeni, F., Häuser, W., Fluß, E., ... & Dincer, F. (2016). EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, annrheumdis-2016.

28. Jung, C. G., & Hull, R. F. (1969). Psychology and religion: West and East. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

29. Galantino, M. L., Bzdewka, T. M., Eissler-Russo, J. L., & Holbrook, M. L. (2004). The impact of modified Hatha yoga on chronic low back pain: a pilot study. Alternative therapies in health and medicine, 10(2), 56.

30. Kabat-Zinn, J., Lipworth, L., & Burney, R. (1985). The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. Journal of behavioral medicine, 8(2), 163-190.

31. Melzack, R., & Wall, P. D. (1967). Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Survey of Anesthesiology, 11(2), 89-90.

32. Beecher, H. K. (1959). Measurement of subjective responses: quantitative effects of drugs.

33. Patanjali, B. (2015). The yoga sutras of Patanjali. BookRix.

34. Deyo RA. Real help and red herrings in spinal imaging. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 1056-1058.

35. Jones, D. N., Badiei, A., Quinn, S., Ratcliffe, J., Runciman, W., Saccoia, L., ... & Thomas, M. (2012). Reducing the inappropriate use of medical imaging in the emergency department: a NHRMC TRIP Fellowship Project. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiology Oncology, 56, 4.

36. Jarvik JG, Hollingworth W, Heagerty PJ, Haynor DR, Boyko EJ, Deyo RA.Three-year incidence of low back pain in an initially asymptomatic cohort.Spine 2005; 30: 1541-1548.

37. McCullough BJ, Johnson GR, Brook MI, Jarvik JG. Lumbar MR imaging and reporting epidemiology: do epidemiologic data in reports affect clinical management? Radiology 2012; 262: 941-946.

38. Main CJ, Foster N, Buchbinder R. How important are back pain beliefs and expectations for satisfactory recovery from back pain? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010; 24: 205-217.

39. Darlow B, Dowell A, Baxter GD, Mathieson F, Perry M, Dean S. The enduring impact of what clinicians say to people with low back pain. Ann Fam Med 2013; 11: 527-534.

40. Lin IB, O’Sullivan PB, Coffin JA, Mak DB, Toussaint S, Straker LM. Disabling chronic low back pain as an iatrogenic disorder: a qualitative study in Aboriginal Australians. BMJ Open 2013; 3: e002654.

41. Sullivan MJ, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, et al. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain 2001; 17: 52-64.

42. Vibe Fersum K, O’Sullivan P, Skouen JS, Smith A, Kvåle A. Efficacy of classification-based cognitive functional therapy in patients with nonspecific chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pain 2013: 17: 916-928

43. Colloca, L., & Benedetti, F. (2006). How prior experience shapes placebo analgesia. Pain, 124(1), 126-133.