Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis (AIS) is the most common form of scoliosis, widely thought of as a lateral curvature of the spine, it is actually a three dimensional structural deformity of the spine and trunk, which occurs in otherwise healthy children during puberty, cause unknown. The Cobb angle is the conventional measurement of scoliosis as taken from x-ray images in the coronal plane, curvatures <10deg are viewed as normal as they have little potential for progression.

Scoliosis management is usually regarded as successful when curvature progression has stopped below certain limits, however parameters other than progression may play an important role from the patient's perspective.

Traditionally, the treatment options for AIS are outpatient rehabilitation; inpatient rehabilitation; bracing and surgery. In the included studies the outcome of treatments were compared with the natural history or observation (non-intervention). Prospective short term studies have been found to support outpatient and inpatient rehabilitation, no controlled study, neither short, mid or long term, was found to reveal any substantial evidence to support surgical intervention. In light of the unknown long term effects of surgery, Weisse, Goodall. (2008) state that, "a randomised controlled trial (RCT) seems necessary, however, due to the presence of evidence supporting conservative treatments, a plan to compose a RCT for surgical treatment options seems unethical."

The needs of the patient should always be top priority and therefore non surgical treatment options should be exhausted, especially when evidence concerning the natural history of AIS is well documented and provides reassurance about the long term effect of untreated AIS for most patients. People with AIS do not have an increased mortality rate when compared to those without, nor do they have a higher risk of hypertension, neurological Impairment or functional difficulties. Pulmonary symptoms such as shortness of breath may be associated with AIS however sufferers usually present with a Cobb angle of >80deg (a relatively large clinical deformity) or with a greater rotation component, which correlates with decreased chest wall range of motion.

Further to this, respiratory failure as a result of AIS has been shown to only occur in patients with a Cobb angle of >110deg. The prevalence of back pain in individuals with AIS is reportedly higher than those without, however pain does not correlate with curve size or arthritic change. Self image was found to be significantly worse in those with AIS compared to those without, especially in teenage girls with small curves, however there was no increase in depression in those with AIS compared to those without. Curve progression does not seem to be influenced by pregnancy and childbirth.

There is some evidence supporting outpatient physiotherapy intervention and inpatient rehabilitation in terms of changing the signs and symptoms of AIS, best results were observed when treatment lasted for 4 - 6 hours per day. There is also some evidence for brace treatment, best results were observed when braces were worn for 23 hours a day during a period of fast growth. Studies which backed the use of surgery to treat those with AIS used the outcome measures related to Cobb angle and aesthetics (even though clinical measures of scoliosis rarely correlate with patients' perceptions of appearance).

The evidence suggests that in no case should an indication for surgery be based entirely on the Cobb angle. Studies which backed a conservative approach to management of AIS instead use outcome measures related to function, pain and quality of life. The only indication found in the literature for surgery is for psychological means, however this seems inadequate as surgery is impossible to reverse compared with subjective beliefs and attitudes concerning self image, which can be altered more easily.

The assumption that there is an indication for surgery, in spite of known short, mid and long term risks, should be made cautiously, especially by those with an ethical responsibility to the patient, as surgical intervention lacks scientific evidence base. Further to this, claims for a RCT regarding bracing also seem unethical due to the fact that allowing growing patients to continue without conservative treatment (a control group) until surgical intervention may be recommended, is absolutely unethical, especially when the problems related to surgery are considered.

Specific questions such as these have arisen from those reviewing the literature; "why do papers lacking scientific justifications, containing detrimental bias that negate the use of alternative conservative measures reach the status of publication, whilst others which do not suffer from such weakness and support the use of conservative treatment have been rejected publication status?" (Weisse, Goodall. 2008).

In light of the conflict of interest many spine surgeons have because of their affiliation with the industry, alternative modern approaches to the problem such as conservative scoliosis specialists, could assess and discuss the benefits and risks of spinal surgery without bias, provide access to conservative rehabilitation and psychological support. Therefore it could be possible that the only evidence based indication for surgery (psychological distress associated with self image) could be ruled out altogether. This seems even more important when one is aware of the risks of surgical scoliosis treatment.

Spinal Surgeons currently recommend spinal fusion surgery for those with AIS presenting with a Cobb angle of >40 to 45deg or have a perceived risk of curve progression (evidence suggests there is no way to accurately predict curve progression). In spinal fusion the vertebrae are accessed via posterior, anterior, or thoracoscopic incisions. These surgical techniques use the spine as a structural scaffold, cementing the steel rods, screws and wires onto the vertebrae with a bone paste aimed at improving overall spine alignment. The choice of instrumentation used to fuse the spine is based solely on the preferences of the individual surgeon.

These spinal fusion surgeries are conducted with the expectation that the operation will heal well and remain sturdy throughout the patient's lifespan. Early attempts at spinal fusion surgery aimed to leave patients with a mild residual deformity but failed to live up to such expectations. Since then aims of surgery have been revised to the more modest goals of preventing progression, restoring 'acceptability' of the clinical deformity and reducing curvature.

Scoliosis surgery has a varying but consistently high rate of complication, which may be under reported considering many long term risks are yet to be investigated. In view of the fact that there is no evidence to suggest the health and function related signs and symptoms of scoliosis can be altered by spinal fusion in the long term, a clear medical indication for this treatment cannot be derived.

Risks of spinal fusion include:

General Surgical Risks

Blood loss, urinary infections, pancreatitis, obstructive bowel dysfunction, neurological damage and death.

Loss of Normal Spine Function

In all spinal fusions there is an irreversible loss of normal active and passive range of movement of the spine, including the non-fused segments. When compared to control subjects, the ability to side flex is reduced by 20 - 60% (Winter et al, 1997). This loss of segmental range of motion has gained little significance in the literature especially in relation to the negative effects upon patient health, function and quality of life.

Winter et al (1997) argued that "it has long been a clinical observation by surgeons who manage scoliosis that patients seem to function well and be relatively unaware of spinal stiffness, even after many motion segments have been fused", however no data in support of this observation is provided. The evidence has actually shown that in conservatively managed cases, pain increases as flexibility decreases.

Strain on Other Vertebrae

The fused spine causes increased strain to be placed on the unfused components of the skeleton and in severe cases, results in stress fractures. More commonly reported are post fusion degenerative changes, which occur in adolescents and adults, sometimes within 2 years after surgery. A higher degree of curve re-alignment results in a higher rate of degenerative osteoarthritis and the high stress on the fused vertebral segments means that even low level forces can cause serious injuries. Surgeons currently recommend that in surgically treated scoliosis patients, trauma physicians should have a high level of suspicion for potential spinal injuries above the site of the previous multi-level fusion.

Post Surgical Pain

Pain is the primary reason surgeons opt for re-operation. The reason for and mechanism surrounding increased spinal pain post surgery is not well understood. But still the overwhelming answer for surgeons seems to be to re-operate. In a study which involved 190 patients, 19% were directed towards re-operation within 2 to 8 years after surgery (Cook et al, 2000). For the 27 patients who underwent re-operation 41% did not report a reduction in pain, and a further 26% were very unhappy with the final outcome (Voos et al, 2001). Pain at the iliac graft site and associated with rib-resection, has also now been formally published; of 87 patients, 24% complained of pain at the graft site, 15% reporting pain to a level which interfered with activities of daily living (Skaggs et al, 2000).

Infection and Inflammation

Surgery related infections and associated inflammatory processes may manifest well after the time of surgery, infections due to surgical intervention have in some instances been detected 8 years later. Of those who develop post surgical infections, 5 to10% of patients develop deep infections at 11 to 45 months after surgery and in severe cases the spinal cord is left exposed to injury (Richards, BS. Emara, KM, 2001 & Tribus, CB. Garvey, KE, 1995). The increased rate of infection now observed may be due to larger instrumentation being used or due to the increased prevalence of multi-drug resistant bacteria found in hospital settings.

Other post surgical issues include; particulate debris from implants stimulating autoimmune responses resulting in bone deterioration, the need for follow up surgery to remove instrumentation as well as infection through blood transfusions required due to the large volumes of blood loss associated with such invasive procedures.

Progression of Curvature

Some curvatures continue to progress after spinal fusion due to faulty instrumentation.

Increased Deformity in the Sagittal Plane

Spinal surgeons have always experimented with different types of instrumentation of increasing size and complexity, however each new process has led to new complications. One problem which continues as a result of spinal fusion surgery, despite changes in surgical implants and techniques, is decompression of the spine or the development of new spinal deformities in the sagittal plane. For example, in those with thoracic scoliosis, reducing lateral curvature can increase the sagittal deformity resulting in flattening of the spine in that region. This surgically related 'flat-back' deformity can lead to pain, range of motion and loading complications as well as ongoing disability.

Increased Deformity of the Torso

The rib hump associated with thoracic scoliosis can increase in response to the force applied to the spine during spinal fusion surgery. Even if the rib hump is decreased immediately post operatively it can worsen and in some instances progress beyond the size of the pre-surgical deformity. In response to this, surgeons use costoplasty to improve the appearance of the rib prominence. This process of rib removal can lead to progressive post surgical scoliosis and further permanent rib cage compromise such as 'flail chest', resulting in reduced chest volume and substantially impaired pulmonary function.

Revision Surgery

In response to the surgical complications outlined above, 'reconstructive,' 're-corrective,' 'revision,' or 'salvage' surgery is often required. Failed spinal fusion surgery has been found to affect more than 50% of treated patients (Hawes, 2006) and among a sample of 25 adult patients, 40% of them required revision (Verven et al, 2001). Even in cases where a solid fusion is obtained by the time of revision, the removal of instrumentation can lead to spinal collapse and even more surgery. Many authors suggest that patients and their parents should be made aware of the likelihood of requiring more than one surgical intervention.

From the patient's perspective and in light of the above evidence, the preferred management plan for AIS would likely be based upon avoiding unnecessary risks such surgery, or to keep it as the final option, once all conservative measures have failed.

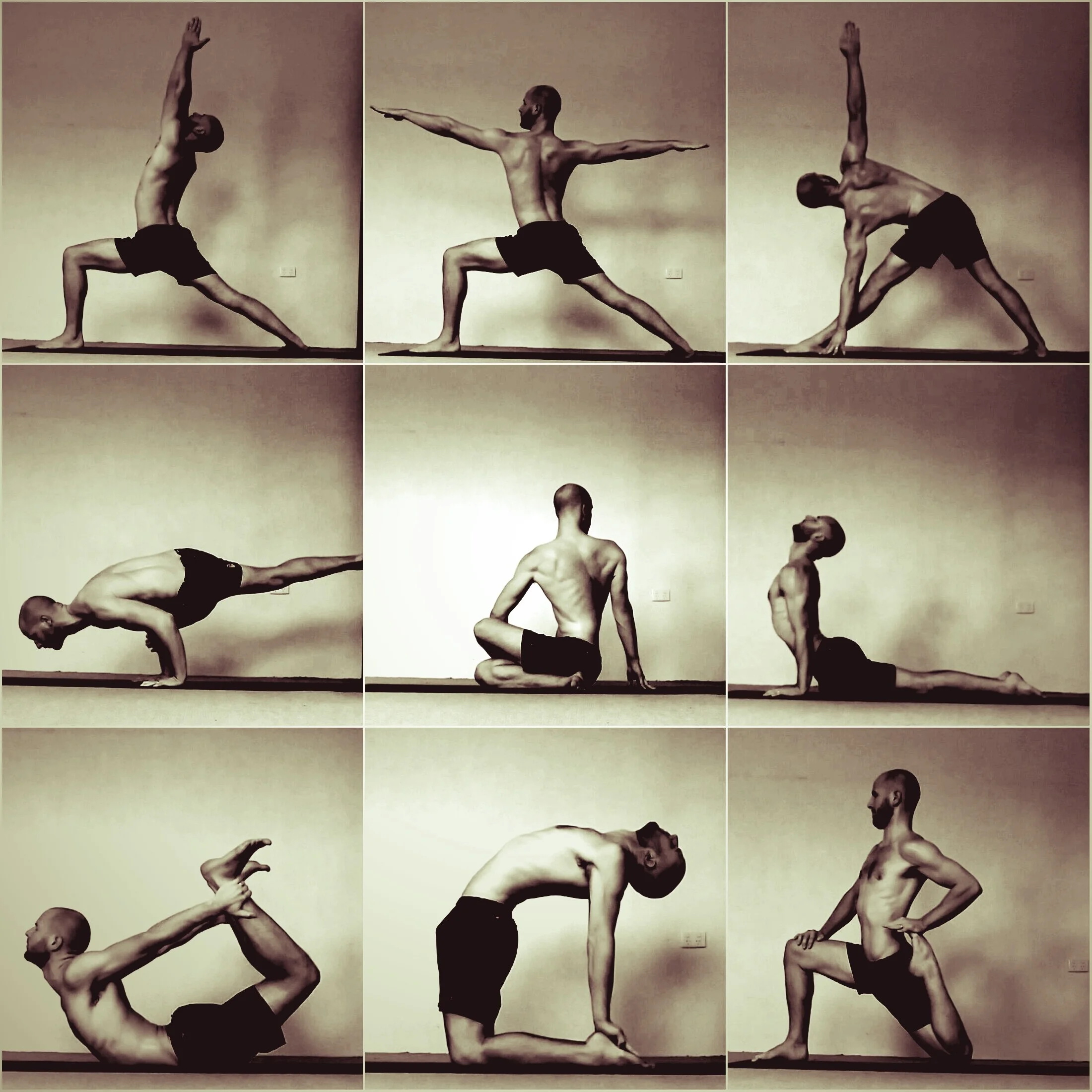

The Qualified and Experienced Physiotherapists at Inner Focus Physiotherapy can work with those presenting with AIS to improve their postural awareness, body alignment, stability, range of motion and movement control. As Exercise Based Physiotherapists we provide clients "with a way of being sensitive to the asymmetries of the body and to deal with them intelligently." (M. Monroe. 2012).

References:

Cook, S. Asher, MA. Lai, SM. Shobe, J. (2000) Reoperation after primary posterior instrumentation and fusion for idiopathic scoliosis, toward defining late operative site pain of unknown cause. Spine; 25:463-468

Hawes, M. (2006) Impact of spine surgery on signs and symptoms of spinal deformity. Pediatric Rehabilitation; 9(4):318-39

Monroe, M. (2012) Yoga and Scoliosis: A Journey to Health and Healing. Demos Medical Publishing, NY.

Richards, BS. Emara, KM. (2001) Delayed infections after posterior TSRH spinal instrumentation for IS. Revisited. Spine; 26:1990-1996

Skaggs, DL. Samuelson, MA. Hale, JM. Kay, RM. Tolo, VT. (2000) Complications of posterior iliac crest bone grafting in spine surgery in children. Spine; 25:2400-2402

Tribus, CB. Garvey, KE. (1995) Full-thickness thoracic laminar erosion after posterior spinal fusion associated with late-presenting infection. Spine; 28:E194-E197

Verven, SH. Kao, H. Deviren, V. Bradford, D. (2001) Management of thoracic pseudarthrosis in the adult: is combined surgery necessary?

Proceedings, Scoliosis Research Society 36th Annual Meeting, Cleveland OH

Voos, K. Boachie-Adjei, O. Rawlins, BA. (2001) Multiple vertebral osteotomies in the treatment of rigid adult spine deformities. Spine; 26:526-533

Weiss, H-R. Goodall, D. (2008) Rate of complications in scoliosis surgery - a systematic review of the Pub Med literature. Scoliosis Journal; 3: 9

Weiss, H-R. Goodall, D. (2008) The treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) according to present evidence: A systematic review. European Journal of Physical Rehabilitative Medicine; 44: 177-93

Winter, RB. Carr, P. Mattson, HL. (1997) A study of functional spinal motion in women after instrumentation and fusion for deformity or trauma. Spine; 22: 1760-1764