By Lee Schneider

Put simply, self-efficacy is the belief that you have the capacity to perform tasks and achieve goals.

When put like this, self-efficacy is a bit of an umbrella term. Saying something like “John has high self-efficacy” is similar to saying something like “john is quite confident”. The thing is, we aren’t really saying what he thinks he’s good at, only that he is generally confident in his abilities.

Therefore, I’d like to talk about task-specific self-efficacy. For example, someone could have a high athletic self-efficacy but a low self-efficacy for public speaking. Furthermore, a single person can have a high self-efficacy for public speaking at a friend’s wedding but low self-efficacy public speaking at a university lecture.

So self-efficacy is both person-sensitive and context-sensitive, meaning that both the person’s traits and the environment they find themselves in is important.

There are four key environmental influences that may influence a person’s self-efficacy.

The first is whether you have performed the task, or similar tasks, in the past successfully - A trained archer should feel more confident in hitting a bullseye from 20m than someone who has never fired an arrow before.

The second is whether you have seen other people, who you deem to be similar enough in capacity to you, perform the task successfully - If you have never fired an arrow from a bow before and you watch another newbie hit a bullseye, then your belief that you can hit a bullseye goes up.

Thirdly, if other people that you trust tell you that you can do it, you are more likely to believe that you can - If the instructor says that they have seen many newbies like yourself hit a bullseye during their first session then your confidence will be increased.

Lastly, your physiological response to the task informs your self-efficacy too. If you start to feel sick in the stomach and get the shakes, or you get a wave of energy and excitement, then this will feed back into your beliefs about your capacity to perform the task.

So your self-efficacy for tasks is influenced by your previous exposure to the task, watching others do it, being told you can do it and the way that you feel prior to, and during, the performance of the task.

Self-efficacy and pain

Self-efficacy can be related to pain also. In the example above, successful completion of the task was hitting the bullseye with an arrow fired from a bow. In pain self-efficacy, successful completion of the task may be performing the task without pain.

If you have the belief that when you perform a certain task it will be painful then you have lower self-efficacy that you can perform that task pain-free.

However, it is slightly more complicated than this. The task has to be something meaningful to you and the pain has to be at a level where it is either preventing you from performing the task or is making the task unpleasant enough for it to negatively impact your wellbeing.

For example, you may cringe at the thought of doing a back-bend, but it also might not be very high on the list of meaningful tasks you need to perform. Furthermore, a rock climber might have the belief that they will get sore fingers from climbing but it doesn’t affect their desire or capacity to go climbing as they know that sore hands is part of the game, at least early on.

Where self-efficacy and pain is relevant is when you have the belief that you can’t perform a task that is meaningful to you due to pain, or you have the belief that when you perform the task the pain is bad enough for it to really affect your wellbeing.

How might this belief form?

Say your job requires you to work at a desk for three hours a day, but you have the belief that you can only work for an hour before your neck pain starts to impact your work. This would suggest you have low pain self-efficacy for the task of performing three hours of desk work.

You will most likely have experiential evidence for this belief in that past experiences of you trying to perform this task has resulted in a sore neck.

You may have witnessed other people in your office have neck pain when they sit for long periods and see that you are in a similar enough situation to them.

A health care professional or someone you trust may have told you that working at a desk for too long “stuffs up your neck”.

Lastly, you may feel anxious and worried when you go to sit at your desk to start work and this will feed back into your belief that you can’t do it.

Why does it matter?

This is important. It matters because your beliefs inform your actual experience of the task that you’re trying to perform. That is, what you believe is going to happen ends up shaping what perceive as happening. Let’s be clear here. I’m not saying that everything you believe comes true. What I am saying is that your beliefs are important in determining the way that you perform a given task and the sensory information that your brain attends to during the task.

The brain is a very clever machine. It is constantly making predictions about what it is likely to experience during a task and weighs these predictions against what actually happens as provided by sensory input. Sensory input is information carried by nerves from throughout the body to the brain that tell the brain what is happening in, and to, the body. So, the brain makes guesses about what these nerve fibers are going to deliver to it and compares those guesses to what they actually deliver.

Can you see that self-efficacy is really just a bunch of predictions about what you think is likely to happen when you do something?

The thing is, the brain is constantly getting it wrong. The world is far too complex and unpredictable for us to carry all the information needed to make 100% accurate predictions of events and their sensory consequences, in the circuitry of our brain. In fact, the brain probably never get it exactly right, rather a scale of wrong-ness. When the predictions it makes about what it is going to experience is wrong it can deal with this ‘prediction error’ in three different ways.

1) It can learn and update its guesses for future encounters.

2) It can choose to pay attention to sensations that confirms its guesses and ignore sensations that don’t.

3) It can act upon the body to change sensations in a way that confirms its guesses.

Let’s put this in the context of pain using the neck pain example above.

If you make the prediction that you will experience neck pain when you sit at a desk for an hour you are more likely to experience that pain. Furthermore, the stronger your prediction the more likely that this will happen.

Let’s say that you’ve been sitting at the desk for 59 minutes without pain and look down at the clock to see that 59 minutes have passed since you sat down. At this point your neck is not providing sensory input that there is anything bad going on there, but due to the clock and your beliefs you have the prediction that it should be starting to hurt.

In this situation your brain can do one of the three things I mentioned above.

1) It can learn from this scenario that it can sit for an hour without pain, thus updating it’s understanding of the capacity to perform this task without pain.

2) It can selectively attend to sensory input that confirms the neck is in pain and ignore sensory input that says otherwise.

3) It can change the activity of muscles and other systems to actively provide sensations that suggests there is pain. This may explain things like muscle “tightness” or muscle guarding in pain.

What I’m saying is that in certain situations, if your pain self-efficacy is low enough, your brain may actually change your experience to suit your beliefs rather than change your beliefs to suit your experience, which is clearly problematic.

What do I do about it?

Clearly the first option the brain uses is more advantageous than the other two. It seems appropriate to update your understanding of the world than to engage in self-deception.

So, changing your predictions appears to be important and this can be done in a few ways, that so happen to mimic the influences on self-efficacy:

1) You can update your predictions experientially by doing the task, or similar tasks, successfully. You can even try to perform the task in alternative environments in the attempt to change contextual factors that influence the predictions you make.

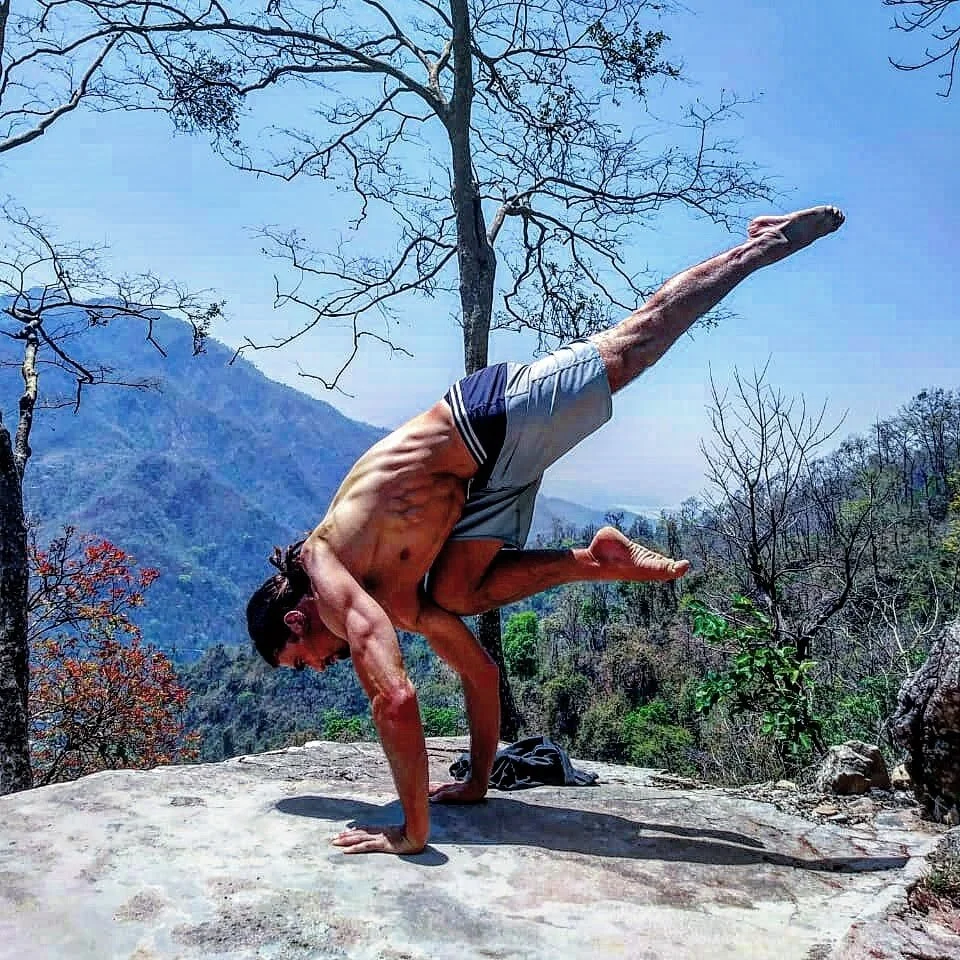

2) You can watch another person do the task successfully and find similarities between you and that other person.

3) You can seek information that is positive, and challenge information that you have that is negative. This is a hard one as there is a lot of scary/dodgy information out there and without formal training it’s challenging to know what is relevant and what is just wrong and harmful. Given that information informs predictions, sometimes it’s best to seek advice from someone who can de-weight predictions that aren’t helpful and add weight to predictions that are helpful.

4) Finally, you can learn strategies to keep yourself calm and relaxed when confronted with a task that you feel you can’t perform without pain. There are many ways to do this such as slowing the breath, being mindful, softening the body and noticing unhelpful thoughts as they arise.

Mindfulness, education and movement

It seems likely that we have a brain that isn’t updating to new information, a collection of beliefs that aren’t helpful and a body that needs to move better.

Therefore, we should make the brain more receptive to the actual sensory consequences of the tasks we perform by practicing mindfulness and developing a non-judgmental awareness of the body. We should find, understand and live by information that frames predictions in a more positive light and disconfirm information that is negative. And, we should move the body regularly, and in a variety of ways, so that we have a body and brain that is conditioned to the physical and sensory consequences of lots of different ways to move and interact with the world.

This, is how you build self-efficacy.

References

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American psychologist, 37(2), 122.

Clark, A. (2013). Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behavioral and brain sciences, 36(3), 181-204.

Den Ouden, H. E., Kok, P., & De Lange, F. P. (2012). How prediction errors shape perception, attention, and motivation. Frontiers in psychology, 3, 548.

Martinez-Calderon, J., Zamora-Campos, C., Navarro-Ledesma, S., & Luque-Suarez, A. (2018). The role of self-efficacy on the prognosis of chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. The Journal of Pain, 19(1), 10-34

Mosley, G. L., & Butler, D. S. (2017). Explain pain supercharged. NOI.

Ongaro, G., & Kaptchuk, T. J. (2019). Symptom perception, placebo effects, and the Bayesian brain. Pain, 160(1), 1.